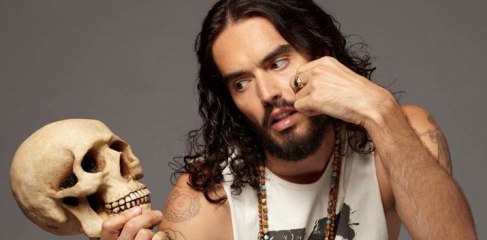

My next blog was supposed to be about the week I’ve spent in Melbourne. It’s on the way, but has been rudely interrupted by everyone’s favourite Halloween-haired, Sachsgate-enacting, estuary-whining, glitter-lacquered, priapic berk (his words not mine) who has been causing a great deal of commotion this week for his New Statesman article and Newsnight interview, encouraging people not to vote, but to take action into their own hands and form an ‘inclusive movement of the left’.

Brand covers a wide variety of topics, from privilege and consumerism, to resource scarcity and economic meltdown. His compelling arguments and master wordsmithing have struck a chord with some and infuriated others, leading to descriptions such as the ‘Jeremy Clarkson of the left’ (my personal favourite). Like him or not, Brand is a master of public relations, a scintillating orator and obviously in possession of a keen mind. So, I thought I’d try and pull out a few nuggets on what sustainability marketers can learn from this latest tyrade:

- Framing is all important: “When people talk about politics within the existing Westminster framework I feel a dull thud in my stomach and my eyes involuntarily glaze.” Not everyone cares about sustainability, in fact, most don’t at all when it’s framed as sustainability (don’t understand), waste (too boring), the future of our planet (too overwhelming). Just because Brand doesn’t care about the politics in it’s current form, doesn’t mean he doesn’t want the system to change. By reframing political reform as a social movement and using himself (pop culture icon that he is) as the messenger, Brand has created a connection with a topic which, he admits, most people (himself included) are ‘disenchanted’ with.

- Joyful relevance: “Serious causes can and must be approached with good humour, otherwise they’re boring and can’t compete with the Premier League and Grand Theft Auto. Social movements needn’t lack razzmatazz.” What sustainability marketing should be all about: mainstream appeal. Not everyone aspires to be a part of Friends of the Earth, or the Labour party, and we know from consumer research that sustainable behaviours are often seen as too difficult or time consuming. Making sustainable behaviour desirable (and not overtly about sustainability) moves it up the ‘to do’ list by creating a ‘pull’. References: Veja, Nike+

- What’s in it for me? “I deplore corporate colonialism but not viscerally. The story isn’t presented in a way that rouses me. Apple seems like such an affable outfit; I like my iPhone. Occasionally I hear some yarn about tax avoidance or Chinese iPhone factory workers committing suicide because of dreadful working conditions but it doesn’t really bother me, it seems so abstract. Not in the same infuriating, visceral, immediate way that I get pissed off when I buy a new phone and they’ve changed the fucking chargers, then I want to get my old, perfectly good charger and lynch the executives with the cable.” Here, Brand beautifully encapsulates the problems of communicating big, overarching issues with little tangible personal impact (think climate change) and illustrates the kind of selective hearing that creates a value/action gap. Communicating around or creating nudges which have a direct consequence for the audience group (like the change in chargers) will always have more impact than trying to connect people with an overarching, wooly concept.

- To become mainstream, you have to be inclusive: “When Ali G, who had joined protesters attempting to prevent a forest being felled to make way for a road, shouted across the barricade, “You may take our trees, but you’ll never take our freedom,” I identified more with Baron Cohen’s amoral trickster than the stern activist who aggressively admonished him: ‘This is serious, you c***.'” (Sorry mum). You just have to say the word ‘hipster’ in a room of people to get a negative reaction from someone. The status driven, premuimised, holier than though take on sustainability cannot become truly mainstream. It creates divides, and lends itself to becoming a fad. We need complementary approaches that normalise, reward and make sustainable living affordable for all to widen its appeal.

.

There is much to disagree with in Brand’s post, but much to take from it too. He willfully ignores the power of brands and consumer spending as a form of democracy. He also selectively disregards new market models which are starting to subvert the traditional ‘shareholders first’ mantra (the social enterprise boom in Brazil, co-operatives and transformational business models such as Unilever’s). I’m cooking something up to write about that shortly. I agree with Brand that marketing can create complexity and confusion which leads to apathy, but it can (as he has done) create conversations, direct passions and distil feelings into clear points of view. Therefore, we would do well to pinch a few learnings from his headline grabbing antics.

Next blog on Melbourne shortly…..